A selection of my prose writing.

Choose a button below to visit a specific article, or just scroll to browse:

Miss Disorientated

Books are being distributed, work is under way and the blackboard is already half-full. The cries of ‘But, Miss…‘ have all been ignored and the children have resigned themselves to their fate.

Whilst your entrance remains yet unnoticed by the mohair cardigan and the untidy bun apparently engaged in filling the remaining half of the blackboard, the back rows egg you into action:

’Go on, Sir, you’ll have to tell her.’

‘She did this with Mr Smith the other day, Sir, and he sorted it out.’

Stung by this suggestion of inferiority, you decide to speak out, but you’ve been spotted.

‘Yes, Mr Jones, may I help you?’

Whilst your brain casts about for a tactful reply, your body does an excellent impression of a bumbling idiot. From behind some immense spectacles her eyes make it quite clear that your intrusion is far from welcome and that your time is running out.

‘Well, Mr Jones?’

You abandon the attempt at diplomacy and leap straight in. ‘I’m sorry, but I believe I’m supposed to be teaching this class now.’

The class in question which has been looking forward to seeing you trounced in a game to love are quite impressed by this late rally.

One unwise pupil gets as far as ‘He’s right, Miss, you see…’ before he’s felled by a look that would have aroused the professional jealousy of a Gorgon.

Her stare turns even icier. ‘I take it you’re quite sure, Mr Jones.’ Your heart sinks as she starts a search through her bag. While the search continues, let me digress: This bag is almost certainly of ethnic origin, but whatever its appearance, its capacity is huge. At any one time, it may contain her packed lunch, some shopping done on the way to school, several sets of marking, a couple of text books, some knitting, a Concise Oxford Dictionary, teaching notes and, somewhere, apparently at the very bottom, her timetable.

It must be confessed that, since the school has moved on to a seven day modular timetable, things are not as easy as they were but, as she waves her timetable triumphantly, the battle is not yet won.

‘There you are, Mr Jones, period three, day seven, I have 3C. I knew you were mistaken.’

‘I think you’ll find that this is day six.’

She rounds on a pupil, ‘What day is it then, Smithers?’

‘Please, Miss, day six, Miss.’

‘Well, why didn’t you say so? I’m missing my lesson with 4A.’

Miss Enthusiastic

What’s this? Your nose twitches as it sounds the alarm bells. A smell redolent of Harrod’s Cosmetics’ Hall has come wafting towards you and that can mean only one thing. Your turn has come; you are about to be enthused at.

The rattle of numerous gold bangles and the glint of ring-encrusted fingers confirms your diagnosis. Already you know that the pile of books for which this time was set aside will remain unmarked whilst you endeavour to look interested and make all the right grunting noises.

‘Oh, Mr Jones, I’m so glad I’ve caught you, because I just couldn’t wait to tell you my news. You’ll never believe it, but little Timmy in your form has just written me a most marvellous poem about a tadpole.’

In one respect, of course, she is quite right. You will never believe it. After all, Little Timmy has the physique of a timber yard and the academic ability to match. In your experience, Timmy has still to master the difficult art of holding the pencil the right way up so perhaps your scepticism is not entirely misplaced.

‘He’s written it with such sensitivity and perception. I feel he’s gone inside the subject and explored it from beneath the surface.’

Your mind protests. ‘Sensitivity and perception’ seem unlikely from one who spends his hours of freedom mugging anything that moves. Further unkind thoughts suggest that the only thing Timmy’s likely to ‘go inside’ is one of Her Majesty’s prisons and as for ‘exploring beneath the surface’, his harassment of the fifth form girls has already led to several complaints.

Pointing these things out is to no avail. The smart tie-neck blouse, the pristine skirt, the painted nails, the bright red shoes and the designer spectacles are all so much aglow with enthusiasm that the whole image before you resembles a cheery ladybird escaped from a Walt Disney cartoon. All this eagerness is there awaiting your positive response. To express your doubts would be to crush without mercy this fragile insect.

‘I’m very glad to hear it,’ you say guardedly as a feeble attempt to show willing. A small enough offering to be sure but it is greeted like a morsel of beef thrown to hungry hounds.

‘Oh, Mr Jones, I knew you’d be pleased. After all, Timmy is such a sweet boy that I really think he deserves all the encouragement we can give him.’

Your thoughts shriek in agony to be released but you keep your tongue in a vice-like grip. A low trick occurs to you.

‘Do you suppose Mrs Smith would consider it for the magazine?’ you say innocently. The effect is magic. ‘Ladybird, Ladybird, fly away home.’

As you settle back to your marking, you grin inwardly at your expertise but somewhere a little discomfort niggles. You can remember a young teacher who was equally enthusiastic about such things. And that teacher bears an uncanny resemblance to you.

Mr Ambitious

Go on. Look up from this paper and have a sneaky glance around. He’s there somewhere and he shouldn’t take much finding.

The one thing he most certainly isn’t is inconspicuous. Amid the tweed, cord, denim and crimplene of the staffroom, his ‘rising young executive’ suit soon marks him out. There he sits ostensibly deep into his Times Educational Supplement. Not for him, though, the desperate flick through the Appointments. Oh no. For him an ‘interesting’ report on teaching Classics to the Tribes of the Southern Sahara is prescribed reading. At his feet sits his black executive case. Like a faithful hound, it follows him wherever he goes. His double-cuffs with their black and gold links peep the regulation half inch below his jacket sleeves. Everything combines to give the impression of used car salesman turned personnel manager.

This sartorial elegance, this immaculate image betrays him. Who amid the broken desk hinges, splinters, chalk dust and chewing gum of a classroom could wear a suit such as this? ‘Has he never seen a classroom?’ you may ask. And a more pertinent question would be hard to find. For, in truth, he sees a classroom as little as possible.

In earlier days, he may have had to sully his image by mixing with the children, but then he found that striding the corridor, purposefully, with clipboard in hand, gave a much better impression. Challenged by those who had to forfeit their own lessons to quell the riot in his abandoned class, he would always have been ‘detained on important business to do with the curriculum’.

Wherever he is, the word ‘curriculum’ is never far away, for his educational gobbledegook can outshine any market trader’s patter. Sentences such as, ‘The essential criterion for rationalising formative educational experiences is defined by reference to the learning associated resources of the individual’, drop readily from his lips.

Nowadays, he teaches a few examination sets. Here he feels his brief is to give these pupils the names of several weighty tomes to be read and send them off to the library to do research. This method is justified by an educational report, Research in the Curriculum: the Way Ahead. He deftly uses such reports to justify everything from rarely marking a book (Oppenheim’s Negative Motivational Responses to Grading) to allowing his classes to dismantle the classroom (Creative Behaviour in the Classroom: a Curriculum Approach).

So there he sits, I’m sure you’ve located him by now, this antithesis of the shuffling, baggy old eccentrics who have long held sway in the groves of Academe. If we mock him, as indeed we do, we must do so gently, for there the future lies.

Mr Majestic

There it goes again, that half-cough, half-clearing of the throat — a timeless piercing sound such as may be used by a bishop to warn a curate that over-enthusiastic preaching is encroaching on a favourite TV programme.

That cough, which even as you read is punctuating your thoughts, has been used, it seems, for generations to warn of its owner’s presence or impending arrival. Like a groaning buoy marking a deadly reef, it sounds both awesome and menacing.

Its perpetrator sits, deep in the unravelling of a brainteaser or the finishing of the Times crossword, the cough rising sporadically and unnoticed from the depths. The final answer pencilled in, he sighs, lays the paper aside and turns to a pile of sixth form essays. Perhaps he mutters a little as he marks but otherwise the concentration is absolute. He seems to have been there, in his chair, since the world began.

I say ‘his chair’ for though no legal right renders that chair his, it could be no more firmly so, if its ownership had been the subject of an eleventh commandment. Occasionally a reckless newcomer may sit there but, although nothing is said and no hostilities are declared, the mistake is never repeated. The King returns to his throne, the bloodless suppression of an ill-conceived revolt behind him.

Heads may come and go but this man is timeless, ageless. Winds of educational change have blown to gale force but nothing can shake his calm equilibrium. In his own words, he has ‘seen it all before’ and it is rumoured that he keeps his gown, cane and mortar board ‘ready for the next time they come into fashion’.

He sits in the staff room like a St. Bernard surrounded by yapping puppies. When all around are flying about in a state of rare excitement, his serenity is all the greater. ‘The gym’s burning down? How kind of you to tell me but I really don’t think I’ll come and watch this time. After all, in 1968 it was the whole science block.’

His glare can silence a school assembly in one second flat and to those who oppose him his use of language shows no mercy. Space permits only one example:

‘Watkins, I have scoured the history books; I have searched the encyclopaedias; I have brought to bear all my not inconsiderable experience in this subject but nowhere, Watkins, nowhere have I found reference to this remarkable piece of history to which you, Watkins, have introduced us. Pray tell us what precisely your evidence is, Watkins, for adorning the battlefield at Waterloo with some character apparently rejoicing in the name of ‘Nap’.’

As he shuffles home in his old mackintosh, the few remaining grey hairs stretching across the broad barren plain of his head, he cuts no figure above the bank clerks, office workers and public health inspectors.

Only in school, his Kingdom, is he so mighty a man.

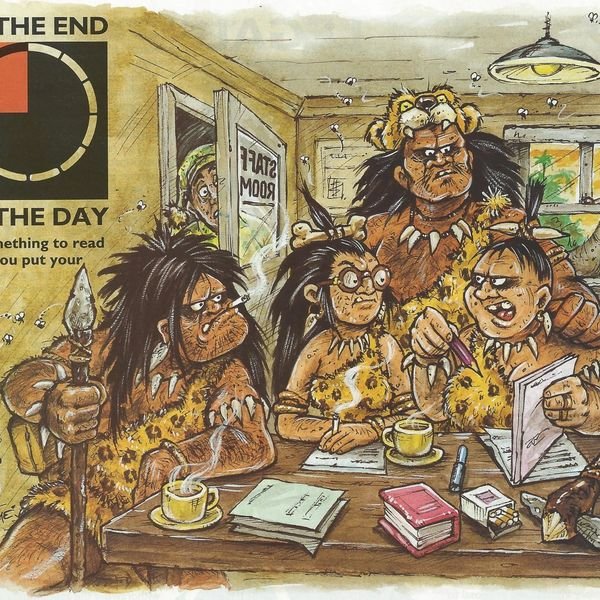

Neanderthal Man

‘Neanderthal Man’, the notice quite unequivocally stated, and indeed, there before me stood, sat, knelt a number of dress shop mannequins all heavily made up to look as Neanderthal as possible. Casting aside the thought that a mannequin, be he/she stuck over with tufts of black hair or no, still looks like a mannequin, I further surveyed the scene. A group of manneq… Neanderthal men and women complete with flint-tipped spears were apparently engaged in some form of group therapy which involved forming a semi-circle around a fire which glowed an unconvincing red. The absence of any other sign of combustion led to the conclusion that they must have been burning the Neanderthal equivalent of smokeless fuel.

Ashamed by the flippancy of my thoughts, I read the description from the notice to the young people clustering so keenly around me, and…What’s the matter? Does that enthusiasm sound unlikely?

Perhaps I should have explained. This was not a real educational visit with bona-fide pupils. This was the summer holidays when the unfortunate children of schoolteachers are dragged all over the country to look at places which might be used for future educational visits. The children clamouring around were my own, and their enthusiasm for my attention had more to do with the nearby ice-cream stall and their need for the purchase price of two ‘99s.

Ice creams purchased and the place assigned a mark out of ten for visit viability, back home we went. Unfortunately, the Neanderthal men also came with us, or at any rate, with me. Try as I might I could not drive from my mind the thought that the whole scene had such a familiar feel to it. There was something about the expressionless disgruntlement, the despairing pointlessness that rang a bell so clearly in my mind. I toyed with ideas of re-incarnation and contemplated the possibility of a previous life as a Neanderthal man, but somehow it didn’t seem very likely. Mercifully, for I’m sure I would have been bereft of sleep else, the answer came to me as I climbed into bed that night.

It was delightfully simple. Take away the fake fire, replace it with a school table of the library type and there you have it—the staff meeting, recreated in glorious technicolour before your very eyes.

I can’t go back again. I’d never be able to resist the temptation to add a subtitle to that self-important little notice. Still, its legacy is with me from now ‘til the day I die, and, like the Ancient Mariner, I must pass on my curse.

During your next staff meeting, when the ‘up and coming’ are waxing voluble in the hope of furthering their careers; when time has stretched to lengths that even relativity couldn’t predict (I was once at a staff meeting when the church clock opposite gave up in despair and chimed 24); when your agenda paper has no more room for doodles, sit back, look around and remember a little notice. It bears only two words: ‘Neanderthal Man’.

DFEE Press Release (Highly Confidential)

⚠️Not for release until 01/04/2012. All authorised personnel receiving this release should keep its contents secure until the above date. Failure to do so could result in a prosecution under Section 5 of the State Secrecy (Open Government) Act, 1998.⚠️

In order to enhance the status of what has hitherto been known as the teaching profession, it is the intention of Her Majesty’s Government to enact, as soon as is possible, legislation to change the working conditions of teachers in both maintained and independent schools. Whilst policy has yet to be decided in every detail, the main elements in the plans of Her Majesty’s Government are as outlined below.

1. NOMENCLATURE

It has hitherto been the practice to refer to members of the aforementioned profession as teachers. (The terms, schoolmaster and schoolmistress, being politically incorrect, have already fallen into disuse.)

Henceforth, it is the Government’s intention that all members of the profession are to be referred to as Learning Acquisition Guides (or LAGs), a name that aptly describes their new role.

Those formerly known as Senior Teachers will not be called Old LAGs, as that phrase has unfortunate connotations. They will instead be Senior LAGs (or SLAGs).

The title Head Teacher will be replaced by Senior Manager in Educational Guidance or SMEG. In the short term, where it is felt that this may be misunderstood by the public, it will be permissible to use the phrase, SMEG/Head.

Her Majesty’s Government is sure this change in nomenclature will raise the status of LAGs above that of mere teachers.

2. PUBLIC PERCEPTION of LAGs.

Her Majesty’s Government has been acutely aware that the extended holidays enjoyed by LAGs have long been a cause of unrest between the profession and the public at large. It has therefore decided that all LAGs will work an extra five weeks a year. This will have the following ‘knock-on’ effects..

i. Schools will remain open all year except for three ‘breaks’ of ten days across Christmas, Easter and in the mid-summer after GCSE examinations have been completed. Any further annual holiday up to the permitted maximum may be taken by arrangement with the school’s SMEG/Head.

ii. The old linkage between a LAG and his/her specialist subject will, as a result, cease. The Government believes that the skill of LAGs, and indeed SLAGs, lies in their ability to guide learning acquisition regardless of the subject being learnt. It will be the duty of the SMEG to arrange a shift system whereby all available staff members are used to cover the timetables of colleagues who are on holiday.

Her Majesty’s Government is sure that LAGs will welcome this opportunity to silence all the tedious public moaning about their long holidays.

3. AFTER SCHOOL PROVISION

Her Majesty’s Government acknowledges the desire of parents to have as little to do with their offspring as possible. In order to further shorten contact time, all LAGs will be required to remain on school premises until 19.00. The period from 16.00 to 19.00 will allow LAGs to entertain pupils by providing suitable extra-curricular activities.

In order that pupils might readily perceive the difference in roles that the member of staff is undertaking, after 16.00 the title LAG will no longer be used. Between 16.00 and 19.00 the LAG becomes an After School Supervisor (or ASS).

Her Majesty’s Government is sure that all LAGs will welcome the opportunity to spend further unpaid time with their pupils.

© Department for Educational Entertainment

Walsingham Reflections No.1

With the Walsingham day coming up, this seemed a good time to start what I hope will become an occasional series of articles about the ‘real’ Walsingham. By which phrase I mean the small Norfolk village which somehow manages to intermingle its own village life with the demands of being a huge centre of pilgrimage. Sometimes it is not a happy union, but that is a subject for a future article. For the moment, let me begin by establishing my own Walsingham credentials.

According to my mother (and she should have known), I was conceived, owing to an error in a Roman Catholic calendar, at Walsingham. Knowing my mother, it is more likely that she’d got her dates muddled somewhere along the line, but the fact remains that I arrived, a somewhat unplanned addition to the family, nine months after an Eastertide pilgrimage to Walsingham. My parents were both Norfolk dumplings and regularly enjoyed pilgrimages to the R.C. shrine as a way of returning to the county of their birth.

Let us move on swiftly through a number of years to the early seventies when I joined my parents (now Anglicans) in a number of pilgrimages to Walsingham. I was captivated by the place and, having passed through the agnosticism of the teenage years, found my faith again in the Holy House, a place which seemed to exude everything I had found missing in the intervening years.

In 1977, my parents retired and bought a house in Cleaves Drive, Walsingham where they were to live for the rest of their lives. In 1979, I bought a house in nearby Fakenham, and it was at that stage that I began to become involved with the life of the village. My parents had made the conscious decision that they would be villagers and not ‘shrine-ites’. At that time, many people retired to Walsingham to immerse themselves solely in the life of the shrine. It is fair to say that within the village there was some resentment of such people. My parents were determined to be part of the village and that is what they became.

With them, I joined the congregation of St Mary’s and I remained associated full time with the village until 1994 when we moved to Ringwood and St Stephen’s. In 1998 we sold the house in Fakenham though we returned frequently to Walsingham to visit my mother. After her death in 2000, our direct links to Walsingham ceased, though we still like to return there when we can.

If you were to visit St Mary’s and follow the path to the right as you face the west door, you would come to the disabled parking area. Should you turn east and start walking through the gravestones, in that area you would find two grey slabs, one to Denis Edmund Clarke and one to Carolyn Elizabeth Clarke, respectively my father and my wife.

Helen, my daughter, is one of very few to have been confirmed in the Holy House at Walsingham; my son Paul was my boat boy at many a grand occasion and my association with the Richeldis Singers is what caused me to end up in St Stephen’s choir – a huge privilege- so I have much for which to thank Walsingham. I hope to share in future articles some of the up and downs of life in this extraordinary village.

Walsingham Reflections No.2

The day dawns bright and early… or so we hope. The village is abuzz with a sense of anticipation. The Cadets are being put through their final rehearsals by the war memorial; Wally, the village donkey, has been moved from his home in the butcher’s field so it can become a car park; ‘Charlie’ Brown, the village bobby, ready for a day of foot counting, has been ‘reinforced’ by his colleagues from Wells; by the village pump, the protestors from Dereham are unfurling their spite-filled banners; coaches and cars begin to queue out along the road to Houghton St Giles. It is, of course, the day of the National Pilgrimage.

Those who have been to the National Pilgrimage will know what a wonderful day it is, but, let me tell you this: you have not experienced the National in all its glory until you have seen it from behind the counter of the Shrine shop.

Nowadays the Shrine Shop is a very slick operation with elegant display spaces and the services of a professional manager. It was not always thus. I came to the shrine towards the end of its early, amateur, volunteer-based phase where operations were run by well-intentioned devotees rather than by professionals, and, although it all lacked efficiency, it did have a certain charm of its own.

My parents were both volunteers at the Shrine shop and so, when National day came along, I was drafted in to help. There were perhaps half a dozen of us fighting over one till and the stockroom had to be seen to be believed. The box for every piece of statuary in the shop was there somewhere, but the system for finding it was not. In comparison, needles in haystacks seemed easy prey.

When we opened, there was already a large queue on the doorstep. ‘I ent seen nowt like it since t’co-op sale,’ a Yorkshire pilgrim was heard to say. And so the floodgates opened and we were immediately swamped. Medallions vied with rosaries for our attention. Tasteful icons jostled with plastic ‘Virgin Mary’s in robes of garish blue. Prayer cards and pens; books and breviaries; necklaces and neck ties – all washed towards us at the counter and, Canute-like, we tried to stem the ever-advancing tide.

During the procession and service, we closed – a welcome respite. The shop was a convenient viewpoint, and, despite the unpleasant cries of the protestors close outside the door, it was good to see the joyful faces of all who passed by.

The service over, the floods returned. Many were now in a hurry to get back to coaches and so the pressure was further increased. Now, this is a cultural, not a racist, observation, but ladies of West Indian extraction, it seems, all like to buy the same thing, and once one has bought a plastic statue of Our Lady (you know, the one which revolves whilst playing the Lourdes Hymn), so a dozen others are clamouring for the self-same article. Do we have enough in stock? Yes. Can we find a dozen identical boxes to put them in? Not a hope. Deep is the suspicion on the faces of the good ladies who have to settle for bubble wrap instead of a box, but in the end all leave happily enough.

We close and rest our weary limbs. The Cadets rowdily disperse, glad to be freed from the discipline of the day; Wally returns to his field and enjoys a good bray to let everyone know he is back; ‘Charlie’, alone again, checks his estimate of the crowd – a magic number arrived at by counting feet and dividing by two. The protestors pack up and leave to spread their message of intolerance elsewhere. The cars and the coaches bear away tired but joy-filled pilgrims, clutching with them their hard-won souvenirs of the day.

Sometimes I like to think that somewhere in Birmingham, Basingstoke, or wherever, a mantelpiece still bears a statue that I sold. (It could be the one where Mary, surrounded by an arch of flashing lights, cradles the baby Jesus to the strains of a tinny version of ‘Away in a Manger’.) And somehow I can’t help but hope that that statue gives to its owner, not only the joy of a National Pilgrimage remembered, but also the focus for a continuation of faith.

Walsingham Reflections No.3

[I hesitated before writing this piece under the ‘Walsingham Reflections’ title because it is rather more about me than about the village, but I think you will understand by the end why I decided it is appropriate.]

Singing church music seems to have been a large part of my life. When I was very young, we were Roman Catholics and, in those days of the Latin Mass, I was inspired to join in loudly with the singing. However, without the necessary command of Latin, I settled for the next best thing which was an extract from a popular song of the time. I can only imagine my parents’ embarrassment when saddled with a son who, whilst everyone else was singing the Tantum Ergo, was roaring out a chorus of ‘Close the door, they’re coming in the window. Close the door, they’re running up the stairs’.

Whether that had anything to do with my parents’ eventual defection from Rome, I can’t be sure, but the next step was to join the choir of St Mark’s, Mansfield, then a church of good Anglo-catholic tradition. For some years I sang there under the direction of the interestingly-named, Mr Jelly. (Not a Roger Hargreaves creation, the poor man must have suffered somewhat from his name. I remember his annoyance when the birth of his second son was announced in the local press under the headline ‘Another Jelly Baby’.) In summer, we trebles used to gather early for choir practice and enjoy a game of cricket against the church wall. A hazard of the pitch was a dark set of steps leading down to a boiler room. The area at the bottom was often used by passing drunks (and probably the occasional choirboy) as a urinal. No one wanted to venture down into ‘the pit’ and so the suitably ecclesiastical-sounding ‘He who putteth, getteth’ rule was added to the Laws of Cricket.

At the age of eleven, I became a boarder at Southwell Minster Grammar School. Arriving too late to be part of the cathedral choir proper, I was drafted into the school choir which sang every morning in the cathedral. This was made up of the cathedral choristers, augmented by a few others in my situation, with the under parts provided by the senior ex-choristers. When my voice broke, I began to sing tenor with the school choir and also joined the choir of Holy Trinity, Southwell – a rather evangelical establishment, but with a strong choir and a very sound musical repertoire.

After seven happy years at Southwell, I arrived in Bournemouth where I joined the Bach Choir. Practice was at St Andrew’s, Boscombe, hardly a stone’s throw away from my digs in Crabton Close Road. I remember an occasion when we sang at St Stephen’s. We were up in the gallery and part of the concert was Rubbra’s ‘Tenebrae’. The occasion was gloriously atmospheric with St Stephen’s wonderful acoustic playing its full part.

A year’s teacher training in Worcester followed during which I sang with the Philomusica. In a scheme of fiendish devising, small groups of singers would meet in half a dozen different locations around the ‘Three Choirs’ area. Each choir would sponsor a concert and all groups would learn the music for it. Then the groups would unite to perform. In that year I performed in all six concerts and learned some of the great choral masterpieces. Elgar’s ‘The Apostles’ and ‘The Kingdom’, Vaughan Williams’ ‘Dona Nobis Pacem’ and ‘G Minor Mass’, and the then newly-published Haydn’s ‘Missa Sancti Nicolai’ all stand out as highlights. That year too saw my only venture into operetta when I sang the role of Menelaus in the college’s production of Offenbach’s ‘La Belle Helene’.

My first teaching post in Croydon was, as far as singing was concerned, a rather fallow period. I joined the school’s chapel choir, but did no other singing.

By now my parents were resident in Walsingham and, in Norfolk for the Christmas holidays, I decided to go to a concert in St Mary’s by the Richeldis Singers. All I knew about this group was that they were led by Jack Burns, then organist of both the Shrine and St Mary’s. It was a snowy night and, when I arrived, I was met by an anxious Jack.

‘I hear you sing tenor,’ he said. (Village bush telegraph had obviously been working overtime.)

‘Er, well, sort of,’ I replied. At which point a sheaf of music was thrust in my hand and that was that. One of his two tenors was stuck in the snow and I was to be the substitute. Thankfully I managed to acquit myself sufficiently well for Jack to declare himself satisfied and to invite me to join on a permanent basis. Such was my baptism of fire into the Richeldis Singers.

Little did I know then just how much part of my life Jack and his singers would become. The group had started with a few girls taught by Jack who had expressed a desire to do more singing out of school. When I joined, it was still very much an ad hoc set up, but already the Singers were being used to provide music for high days and holidays at both the Shrine and St Mary’s, neither of which had a resident choir. Over time, we started to rehearse regularly and to sing services and concerts all over the county. One Christmas Jack phoned and asked me if I could give one of the sopranos a lift to a concert. I was of course happy to oblige. Now, Carolyn (one of Jack’s original young pupils) and I had known each other across the choir for about three years and had shown not a glimmer of interest in each other. Suffice it to say that by the time I dropped her home that evening, we had a date booked, and, although she stood me up for that one, things did develop and, by mid-January we were engaged, and in July, we were married. Jack, of course, played the organ for our wedding. (Sadly, just nine short years later, Jack was also to play for Carolyn’s funeral – but that, as they say, is a whole other story.)

Under Jack’s direction, the Richeldis Singers began to sing long weekends at cathedrals covering for their resident choirs’ holidays. I have happy memories of Lichfield, Norwich, Chester, Salisbury, Derby, Southwell (to name but a few), and of Westminster Cathedral where we were somewhat awed to be greeted personally by Cardinal Archbishop Basil Hume. Not that the local village churches went unattended and we enjoyed our visits to these too. Epiphany Carols at Binham Abbey set the bench mark for sheer coldness; an outdoor Mass at North Creake Priory was probably the noisiest, given that several geese decided very vocally to join in; a candlelit service in the tiny chancel at Glandford was probably the most cramped, but also the most atmospheric.

When I moved to a post in Ringwood, it was Jack who spoke to a friend of his and said he knew of a tenor who would be looking for church choir in the area. That friend was Ian Harrison and so it was that I became part of St Stephen’s choir, a privilege of which I have yet to feel worthy.

As I write this (though it may not be published for a while), I am waiting to make a journey up to Norfolk to attend Jack’s funeral. There is so much more I could say about him, but space is lacking, so I hope you will forgive me for making use of what remains to pay tribute to a man whose friendship and inspiration touched and enriched my life and the life of Walsingham in so many ways. May he rest in peace.

Walsingham Reflections No.4: Bells…

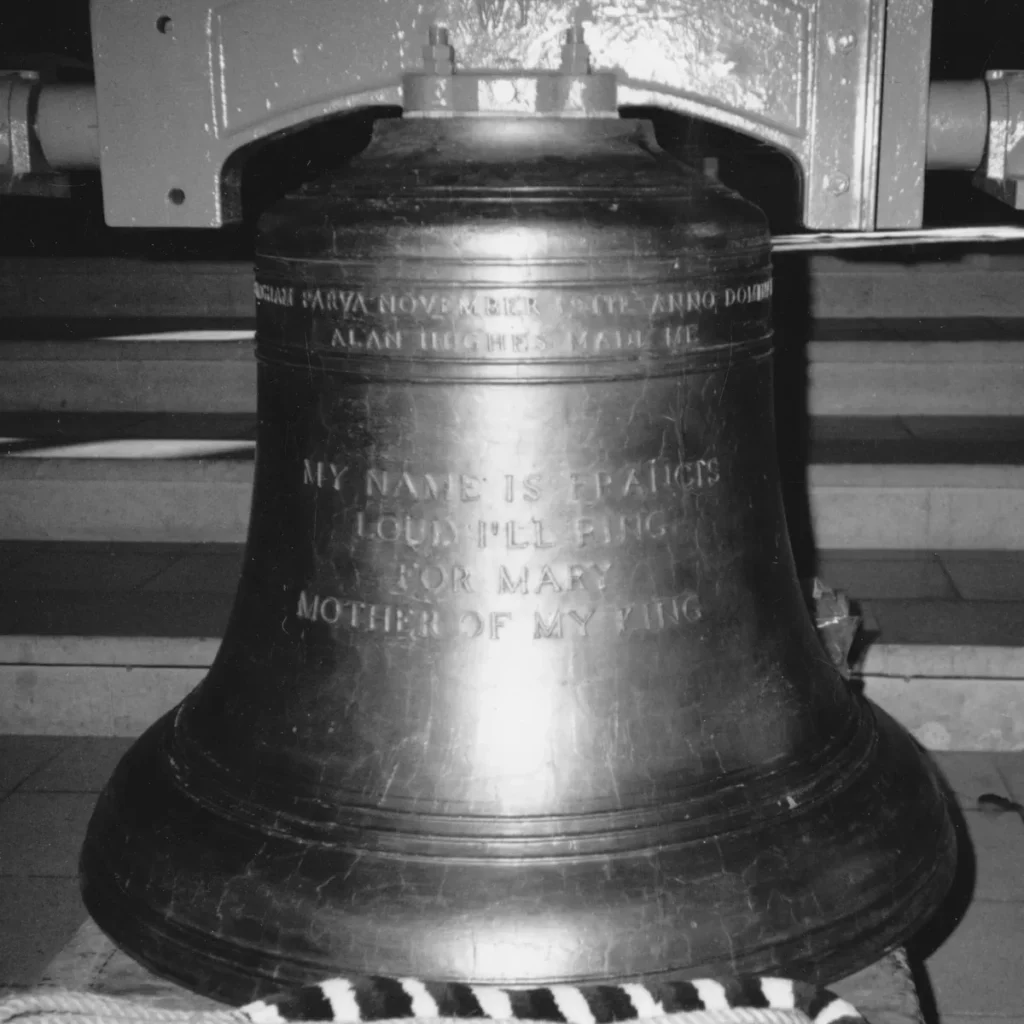

WALSINGHAM PARVA NOVEMBER 19TH ANNO DOMINI 1987

ALAN HUGHES MADE ME

MY NAME IS FRANCIS

LOUD I’LL RING

FOR MARY,

MOTHER OF MY KING

So reads the inscription on the Treble bell of St Mary’s, Little Walsingham. Francis was added to St Mary’s tower in 1987 to turn Norfolk’s heaviest peal of five bells into a peal of six and he heralded a new era of bell-ringing at the church. For many years, the bells had been silent but Fr John Barnes, then the parish priest, decided that regular ringing should be reintroduced. A small band of locals was formed under the captaincy of an experienced ringer and, as a former bell ringer, I was asked to join. Within a short time, the five bells were once again heard ringing out over the village.

Francis was raised into the tower after an impressive dedication service at which I sang as a member of the Richeldis Singers. I then slipped out to join the ringers so that Francis could be ‘greeted’ by his older companions. A little while after Francis had been hung, ‘Songs of Praise’ was broadcast from St Mary’s and I could be fleetingly glimpsed ringing away at my favourite bell, the fourth. The fourth at St Mary’s was of a weight that suited me, but was also ‘odd-struck’* making it slightly more challenging to ring.

At first our little band just rang ‘call changes’. In this sort of ringing, the tower captain calls out the changes to the order in which the bells are to be rung. The bells then stay in that order until a new change is called. That is simple enough and I could cope quite happily. However, we soon progressed to ‘method’ ringing… or perhaps I should say that they progressed to method ringing. In this, the order of the bells changes unheralded according to a numerical method. I had come across method ringing earlier in life, but had never tried it. At Walsingham I was soon left behind. What amazed me was that the local farm workers (whose intellect I had every reason to believe inferior to my own) took to it like ducks to water. ‘That’s simple, borr,’ they used to say. ‘Yew jest hev to foller the bell thet do foller yew.’ Simple it may have been, but it was a skill I never fully mastered.

My first association with bell-ringing had begun some time before, during my schoolboy years at Southwell. Once I had reached the exalted heights of the fourth year, becoming part of the ringing team at the Minster was an opportunity open to me. Now, this is not the moment for a treatise on bell-ringing, but a bell rung properly describes a circle from mouth upright to mouth upright and then back again, causing the clapper to strike the bell once per revolution. Given that bells are very heavy chunks of metal, a great deal of care is needed in the handling of them. The cartoon image of a bell-ringer being hauled off his feet towards a very small hole through which he clearly will not fit is not entirely without factual foundation. However, under the careful tutelage of the tower captain, I did manage to learn to ring a bell in reasonable safety.

Death by bell rope was, however, not the only hazard to be faced. To reach the ringing floor at Southwell, one climbed a long, spiral stairway buried within a corner of one of the transepts. The ringing floor was at the bottom of the central tower. Indeed, if you were to stand inside the Minster at the central crossing and cast your eyes heavenwards, you would find yourself looking at the underside of the ringing floor. To get from the corner of the transept to the tower involved a walk along the narrow clerestory, the uppermost of the three arched arcades which ran round the nave and transepts. On one side, all that stood between you and a plummet to certain death was a thin-looking metal handrail. I have no head for heights, and I dreaded this part of the journey. Even worse, a couple of years after I left Southwell, it was discovered that the whole ringing floor was unsafe, and it had to be replaced. Death, apparently, was stalking me round every corner!

To get back to Walsingham: When my wife, Carolyn, died, the ringing team went to great efforts to ensure the bells were rung half-muffled at her funeral. To do this, a leather pad is tied on one side of the clapper on each bell. (This is a dirty and dangerous job involving crawling about under the bell frames.) When the bell is rung, on one revolution the bell sounds clearly; on its return the clapper strikes the bell through the leather pad and produces a mournful, muted tone. If you were among the 2.5 billion people who watched Princess Diana’s funeral on television, you may remember hearing the bells of Westminster Abbey being rung in this way. It is a truly haunting sound.

The Shrine church, incidentally, has a carillon system in which small bells are struck by hammers when the ropes are pulled. The ropes come together at a central rack. In this way, one person can ring all the bells. I think that nowadays this system is mechanized, but when I was there, a man called Len faithfully used to ring out hymn tunes by following the numbers given on his chart. It was an act of service that brought pleasure to many.

By the time I left Norfolk, ringing at St Mary’s had stopped. The team had dispersed and the bells were silent again. I’m not sure what the current situation is, but I do hope that Francis and his companions are still in use. They may not be popular these days with those who like a Sunday lie-in, but for me, the sound of church bells ringing out in the morning air is part of our heritage we should be reluctant to lose.

* ‘Odd-struck’ describes a bell that rings later on one revolution than it does on the other. This can often be caused by a slight misalignment in the clapper. The ringer has to allow for this in order to maintain a consistent gap between his bell and the bell he follows.

[Footnotes:

· If you are wondering why the ellipsis after the title, ‘Walsingham Reflections 5: …and Smells’ will follow in a future edition and will finish this series of articles.

· In researching for this article, I could not establish the year of Francis’ dedication because it is hidden on the photograph. An email to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry (of which Alan Hughes is the owner) elicited a prompt and courteous response. I wish to record my grateful thanks for the help received.]

Walsingham Reflections No.5: … and Smells.

I have at home a picture, taken at the dedication service for Francis, the bell about which I wrote last time. It shows my father in his accustomed role as thurifer for one of St Mary’s teams of servers. When he died, not long after the photo was taken, I was asked if I would like to take his place on the team and so I returned to serving at the altar. My son Paul became my boat boy and I continued to serve at St Mary’s until we left Norfolk.

Unlike St Stephen’s which is beautifully designed for the East-facing rite, St Mary’s, following the fire, was able to be redesigned to accommodate a West-facing rite. It has a large, spacious chancel with plenty of room for an additional altar and, while I was there, the services were almost exclusively West-facing. How St Stephen’s servers would enjoy the space at St Mary’s! Mind you, if St Stephen’s were to have as many concelebrating priests as St Mary’s has in high season, the sanctuary would be crammed to overflowing.

Those who enjoy the smell of incense probably have little notion of the trials and tribulations that a thurifer faces. To begin, lighting the charcoal can be a challenge in itself. Get it too much alight and it burns away before the end of the service; too little and the incense just stifles it. Assuming you have the coals nicely glowing, the next problem you have no control over. Some priests are budget-conscious and use about three grains. You can wave the thurible about as much as you like, but three grains will not produce enough smoke. There is nothing worse than censing with a smokeless thurible. Other priests however like to use several spoons’ worth. Then you daren’t move the thurible at all because every slight waft produces great billows of smoke and the church soon begins to look as if a sea fret has moved in. Swinging the censer is also a necessary evil. It helps to keep the charcoal glowing and admittedly adds to the ceremony of a procession, but I cannot be the first or last thurifer who has managed to catch the censer on the ground or other obstacle, thereby sending a shower of burning hot coals flying out among the faithful.

You will have noticed (if indeed you have pursued this far into the article) that earlier I slipped in the phrase ‘returned to serving at the altar’ and here I must again go back to Southwell days. Arriving at senior school, age eleven, I was unusual in that I was already confirmed. (Long story short: as a Roman Catholic I had been receiving communion for some years before my parents became Anglicans, so our new parish priest sought dispensation for me to be confirmed promptly. It didn’t after all make any sense to deny me a sacrament I had already been receiving.) Those boys at Southwell who were confirmed were offered the opportunity to become servers in the Minster. The main commitment was to serve the seven o’clock morning Mass in the cathedral. Attendance was vital as often there was only you and the officiating priest at the service. Without you, the service could not be said.

If you are a health and safety enthusiast, this may be the time to look away, because, as I think back on it now, it is startling how different attitudes to such matters were then. Life in the boarding house routinely began at seven when the duty master came round to wake the dormitories. As that day’s server, you were given the servers’ alarm clock which was set for half past six. While the rest of the boarding house was still asleep, you did your ablutions and took yourself off either down a country lane or through the slowly-waking, almost-deserted town to the Minster. (Once, when I had set the alarm wrong, I found I’d arrived at the Minster an hour early. It was a cold wait until the priest arrived with the key.) Alarm clock malfunctions aside, you entered through a side door and introduced yourself at the Sacristy to the priest who was officiating that day. Often you and he would the only people in the Minster. Having robed and processed to whichever chapel was designated for that day’s service, you would begin the preparation, serve the Mass and hope to be back at the boarding house for breakfast at seven-forty, or at least not long after. In all the time I was there, I never felt anything other than safe, either on the journey to and from the Minster, or whilst alone in the building with the priest. How horrible it is that we have lost that innocence to an almost hysterical mistrust! Certainly, a school would never be allowed to put a child into those situations these days.

For the most part, serving was a joy. The only moment to be dreaded was when you arrived at the Sacristy and were told that the service was to be in the Bishop’s Chapel. This meant that you would be serving the Bishop himself, though for some reason you were always accompanied over to the Bishop’s Palace by another priest, who stayed and attended the service. The first time it happened, I was a bag of nerves, feeling myself overawed by the presence of this seemingly-great man. Those, however, who have a long memory for ecclesiastical upsets may remember that this particular Bishop of Southwell ended up in some disgrace following a scandal involving a topless dancer. After that, Bishops seemed a less-rarefied race and I never felt quite so much in awe of his successor.

Walsingham… and it is the Diamond Jubilee of the Shrine in 1991. The statue of Our Lady is once again carried in procession from St Mary’s to the Shrine church. I am one of the thurifers in the procession and Paul, aged nine, is beside me as my boat boy. Helen, aged seven, is a flower girl amongst several others strewing petals from a basket to scent Our Lady’s path. It is a happy time and Walsingham is thronging with people, rejoicing in this anniversary. Soon the other people will board their coaches to return to their homes and we will head off to Cleaves Drive to join my mother for tea in St Bavo, her house named after my parents’ favourite Dutch cathedral.

Though we didn’t know it then, time was running out on our Norfolk days and we would shortly be moving away to Ringwood and St Stephen’s. Slowly our links with Walsingham will fade and become the stuff of memory.

When I returned recently with the Society of Mary/ St Stephen’s pilgrimage, I was overjoyed to find that, despite all the changes that have taken place since I first knew the village, Walsingham is still a place full of peace, wonder and happiness. If you have never been, put it on your ‘bucket list’. You will not regret it.

[This, as I stated previously, is the last in the Walsingham Reflections series. I hope you have enjoyed reading them. It has certainly been a pleasure to write them. Many thanks also to Madeleine who has encouraged me in the endeavour even in the face of my own misgivings.]